Ice Damming Defined and How to Avoid It – December 2012

Here is one of the best articles I’ve ever found to describe what ice dams are and how to avoid this potentially devastating condition. – READ BELOW

Home Energy Magazine Online November/December 1996

Out, Out Dammed Ice!

by Paul Fisette

Ice dams cause millions of dollars of structural damage to houses every year, including water damage from roof leaks. There are many ways to treat the symptoms, but proper air sealing, insulation, and attic venting are the best ways to eliminate the problem.

Anyone who has lived in a snowy climate has seen ice dams. Thick bands of ice form along the eaves of homes, causing millions of dollars of structural damage every year. Water-stained ceilings, dislodged roof shingles, sagging gutters, peeling paint, and damaged plaster are familiar results of ice dams.

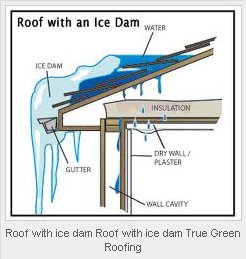

| Ice dams form when heat leaking from the living space below melts snow, which then runs down the roof and refreezes at the edge. Damage can result not only to gutters and roof coverings, but also to the interior of the house. |

Ice dams are not the disease, but rather a symptom of a home’s energy sickness. The cure is energy conservation: keep heat from leaking into the attic from the house.

Ice dams need three things to form: snow, heat to melt the snow, and cold to refreeze the melted snow into solid ice. As little as 1 or 2 inches of snow accumulation on a roof can cause ice dams to form. Snow on the upper part of the roof melts, runs down the roof under the blanket of snow to the roof’s edge, and refreezes into a dam of ice. As more snow melt runs down the roof, it pools against the ice dam. Eventually, water backs up under the shingles and leaks into the structure.

The reason ice dams form along the roof’s edge, usually above the overhang, is straightforward. Heat and warm air leaking from living space below melts the snow, which trickles down to the colder edge of the roof (above the eaves) and refreezes. Every inch of snow that accumulates on the roof insulates the roof deck a little more (about R-1 per inch), keeping more heat from the living space in, which further heats the roof deck. Frigid outdoor temperatures ensure a fast and deep freeze at the eaves. The worst ice dams usually occur when a deep snow is followed by very cold weather.

The Havoc Ice Dams Wreak

Contrary to popular belief, gutters do not cause ice dams. However, gutters do help to concentrate ice and water at the very vulnerable roof eaves area. As gutters fill with ice, they often bend and rip away from the house, bringing fascia, fasteners, and downspouts in tow.

Roof leaks wet attic insulation. In the short term, wet insulation doesn’t work well. Over the long term, water-soaked insulation remains compressed, so that even after it dries, the insulation in the ceiling is not as thick. The lower R-values become part of a vicious cycle: heat loss-ice dams-leaks-insulation damage-more heat loss! Cellulose insulation is particularly vulnerable to the hazards of wetting.

Water often leaks down within the wall frame, where it wets wall insulation and causes it to sag, leaving un-insulated voids at the top of the wall. Again, energy dollars disappear, but more importantly, moisture gets trapped within the wall cavity between the exterior plywood sheathing and the interior vapor barrier, causing smelly, rotting wall cavities. Structural framing members can decay. Metal fasteners may corrode. Mold and mildew can form on wall surfaces as a result of elevated humidity levels. Both exterior and interior paint blister and peel. And people with allergies suffer.

Peeling wall paint deserves special attention because its cause may be difficult to recognize. It is unlikely that wall paint will blister or peel when ice dams are visible. Paint peels long after the ice and the roof leak itself have disappeared. Water from the leak infiltrates wall cavities. It dampens building materials and raises the relative humidity within wall frames. The moisture within the wall cavity eventually wets interior wall coverings and exterior claddings as it tries to escape (as either liquid or vapor). As a result, interior and exterior walls shed their skin of paint.

| Figure 1. Ice dams are caused by a combination of snow, sub-freezing outdoor temperature, and a warm roof over the interior of a building. |

Solving the Problem

Check the home carefully when ice dams form. Investigate the attic, even when there doesn’t appear to be a leak. Look at the underside of the roof sheathing and roof trim to make sure they haven’t gotten wet. Check the insulation for dampness. And when leaks inside the home develop, be prepared. Water penetration pathways are often difficult to follow. Don’t just patch the roof leak. Make sure that the roof sheathing hasn’t rotted and that other less obvious problems in the ceiling or walls haven’t developed. Detail a comprehensive plan to fix the damage. But more importantly, solve the problem that caused the ice dams to form.

You can try to block the flow of melt water into a house by installing a rubber membrane on the roof under the roof shingles. Or you can craft a real solution: keep the entire roof cold, and save energy dollars in the process! In most homes this means: block all air leaks leading to the attic from the house, increase the thickness of insulation on the attic floor, and install a continuous soffit and ridge vent system. Be sure the air and insulation barrier you create is continuous.

Heat loss is often worst just above the top plate, the continuous horizontal framing where exterior walls and ceilings are joined. This is partly because there isn’t room in the corner for adequate insulation. Also, builders are not particularly fussy about air sealing to prevent the movement of warm air up to the underside of the roof surface. Air can leak through wire and plumbing penetrations here, or can come from wall cavities, passing between the small cracks between the top plate and the drywall.

New houses should include plenty of ceiling insulation, a continuous air barrier separating the living space from the underside of the roof, and an effective roof ventilation system. In both new and retrofitted buildings, insulation should be up to local standards. In the northern United States, this is usually at least R-38. A soffit-to-ridge ventilation system is the most effective ventilation scheme for cooling roof sheathing. Power vents, turbines, roof vents, and gable louvers just aren’t as good. Both the baffles on the ridge vent and the sun warming up the roof help drive the air flow out of the ridge vent. Air coming in the soffit washes the underside of the roof sheathing with a continuous flow of cold air.

Insulation retards conductive heat loss, but a special effort must be made to seal warm indoor air inside. In new construction, avoid making penetrations through the ceiling whenever possible. When you can’t avoid making penetrations, or when air tightening existing homes, use urethane spray foam (in a can), caulk, packed cellulose, or weatherstripping to seal all ceiling leaks.

| Figure 2. With proper air sealing and attic ventilation, the roof can be kept cold enough to prevent ice dams. |

Other Options

Sometimes it is not feasible to treat the cause of the house’s problems, and you must treat the symptoms. Steeply pitched metal roofs (common in snow country) in a sense thumb their noses at ice dams. They are slippery enough to shed snow before it causes an ice problem. However, metal roofs are expensive and they are no substitute for adequate levels of insulation.

Self-sticking rubberized sheets can go under roof shingles wherever water could pond against an ice dam: above the eaves, around chimneys, in valleys, around skylights, and around vent stacks. If water leaks through the roof covering, the waterproof underlayment provides a second line of defense.

Sheet-metal ice belts can help, if a shiny 2-ft-wide metal strip along the edge of the roof is acceptable. Ice or snow belts are used for some patch-and-fix jobs on existing houses. The flashing, installed at the eaves, imitates metal roofing by shedding snow and ice before it causes a problem. It works-sometimes. The problem with ice belts is that a secondary ice dam often develops on the roof just above the top edge of the metal strip.

Placing electric heat tape in a zigzag arrangement on the shingles above the edge of the roof is a poor solution. I have never seen electrically heated cable actually fix an ice dam problem. The considerable amount of electricity it takes to prevent ice formation is expensive, and the heating must be done in anticipation of ice dam conditions, not afterwards. Over time, heat tape embrittles shingles, creating a fire risk. It’s expensive to install, too, and water can leak through the cable fasteners. Often the cables create ice dams just above them. Don’t waste time or money on this retrofit.

The worst of all solutions is shoveling snow and chipping ice from the edge of a roof. People attack mounds of snow and roof ice with hammers, shovels, ice picks, homemade snow rakes, crowbars, and chain saws! The theory is obvious. No snow or ice, no leaking water. Unfortunately, this method threatens life, limb, and roof.

Paul Fisette is director of Building Materials Technology and Management at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Home Energy can be reached at: contact@homeenergy.org

Questions?

If you are looking for a new roof or metal roof, then please call

True Green Roofing Solutions or just take a moment and complete

our Request-a-Quote form.

You Have Options!

Don’t wait to schedule your professional estimate!

Call Us Today! (775) 225-1590